Captain Charles Butler McVay, USN, commanding.

There is an English idiom that suggests worse things happen at sea. Nowhere is that more apt than in the sinking of the USS Indianapolis in July of 1945. She was the second last US vessel to be sunk in the war and the circumstances of her sinking, or rather, the survival of her ship's company in the days following her sinking by Japanese submarine, are so dreadful as to give real meaning to the phrase, "worse things happen at sea." They could have been written for the USS Indianapolis alone.

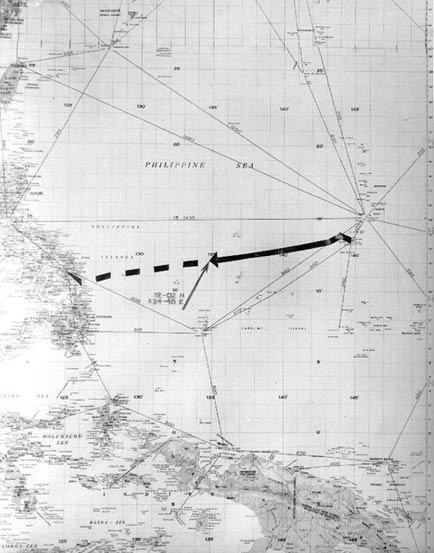

The world's first operational atomic bomb was delivered by the Indianapolis, (CA-35) to the island of Tinian on 26 July 1945. The Indianapolis then reported to CINCPAC (Commander-In-Chief, Pacific) Headquarters at Guam for further orders. She was directed to join the battleship USS Idaho (BB-42) at Leyte Gulf in the Philippines to prepare for the invasion of Japan. The Indianapolis, unescorted, departed Guam on a course of 262 degrees making about 17 knots.

At 14 minutes past midnight, on 30 July 1945, midway between Guam and Leyte Gulf, she was hit by two torpedoes out of six fired by the I-58, a Japanese submarine. The first blew away the bow, the second struck near midship on the starboard side adjacent to a fuel tank and a powder magazine. The resulting explosion split the ship to the keel, knocking out all electric power. Within minutes she went down rapidly by the bow, rolling to starboard.

Of the 1,196 aboard, about 900 made it into the water in the twelve minutes before she sank. Few life rafts were released. Most survivors wore the standard kapok life jacket. Shark attacks began with sunrise of the first day and continued until the men were physically removed from the water, almost five days later.

Shortly after 11:00 A.M. of the fourth day, the survivors were accidentally discovered by LT. (jg) Wilbur C. Gwinn, piloting his PV-1 Ventura Bomber on routine antisubmarine patrol. Radioing his base at Peleiu, he alerted, "many men in the water". A PBY (seaplane) under the command of LT. R. Adrian Marks was dispatched to lend assistance and report. Enroute to the scene, Marks overflew the destroyer USS Cecil Doyle (DD-368), and alerted her captain, of the emergency. The captain of the Doyle, on his own authority, decided to divert to the scene.

Arriving hours ahead of the Doyle, Marks' crew began dropping rubber rafts and supplies. While so engaged, they observed men being attacked by sharks. Disregarding standing orders not to land at sea, Marks landed and began taxiing to pick up the stragglers and lone swimmers who were at greatest risk of shark attack. Learning the men were the crew of the Indianapolis, he radioed the news, requesting immediate assistance. The Doyle responded she was enroute.

As complete darkness fell, Marks waited for help to arrive, all the while continuing to seek out and pull nearly dead men from the water. When the plane's fuselage was full, survivors were tied to the wing with parachute cord. Marks and his crew rescued 56 men that day. The Cecil Doyle was the first vessel on the scene. Homing on Marks' PBY in total darkness, the Doyle halted to avoid killing or further injuring survivors, and began taking Marks' survivors aboard.

Disregarding the safety of his own vessel, the Doyle's captain pointed his largest searchlight into the night sky to serve as a beacon for other rescue vessels. This beacon was the first indication to most survivors, that their prayers had been answered. Help had at last arrived. Of the 900 who made it into the water, only 317 remained alive. After almost five days of constant shark attacks, starvation, terrible thirst, suffering from exposure and their wounds, the men of the Indianapolis were at last rescued from the sea.

Even though the USS Indianapolis was one of the most highly decorated ships of the USN, having won ten battle stars for distinguished service in the Pacific, Captain McVay was court martialled for failing to zigzag and thus endangering his ship. It was no conincidence that of the 700 ships lost by the USN during the WW2, the losses among the surviving crew of the Indianapolis were the highest in the history of the United States Navy, relating to a single ship.

The court sentenced Captain McVay to lose 100 numbers in his temporary rank of Captain and 100 numbers in his permanent rank of Commander, thus ruining his Navy career. In 1946, at the behest of Admiral Nimitz who had become Chief of Naval Operations, Secretary Forrestal remitted McVay's sentence and restored him to duty. McVay served out his time in the New Orleans Naval District and retired in 1949 with the rank of Rear Admiral. Though exonerated of all blame in the sinking by President Clinton in October 2000, he was never forgiven by certain relatives of the fallen. Captain McVay took his own life in 1968.

As regular visitors to my blog will know, I like to embellish my posts with audio visual material wherever feasible, but in the case of the USS Indianapolis may I commend to you this superb archive, thanks to the Discovery Channel, of recordings made by men who survived this most ghastly of all naval ordeals. For best results, click the link in the dark blue panel on the left entitled, "Hear the story in the words of survivors".

Of a ship's company of 1196 men, between 800 and 900 men made it into the water after her sinking. Following 4 days and 5 nights of the most unimaginable horror, 316 men were plucked from the sea. Shark attack was the principle cause of death.

The American Cruiser USS INDIANAPOLIS sank on July 30th, 1945.

No comments:

Post a Comment