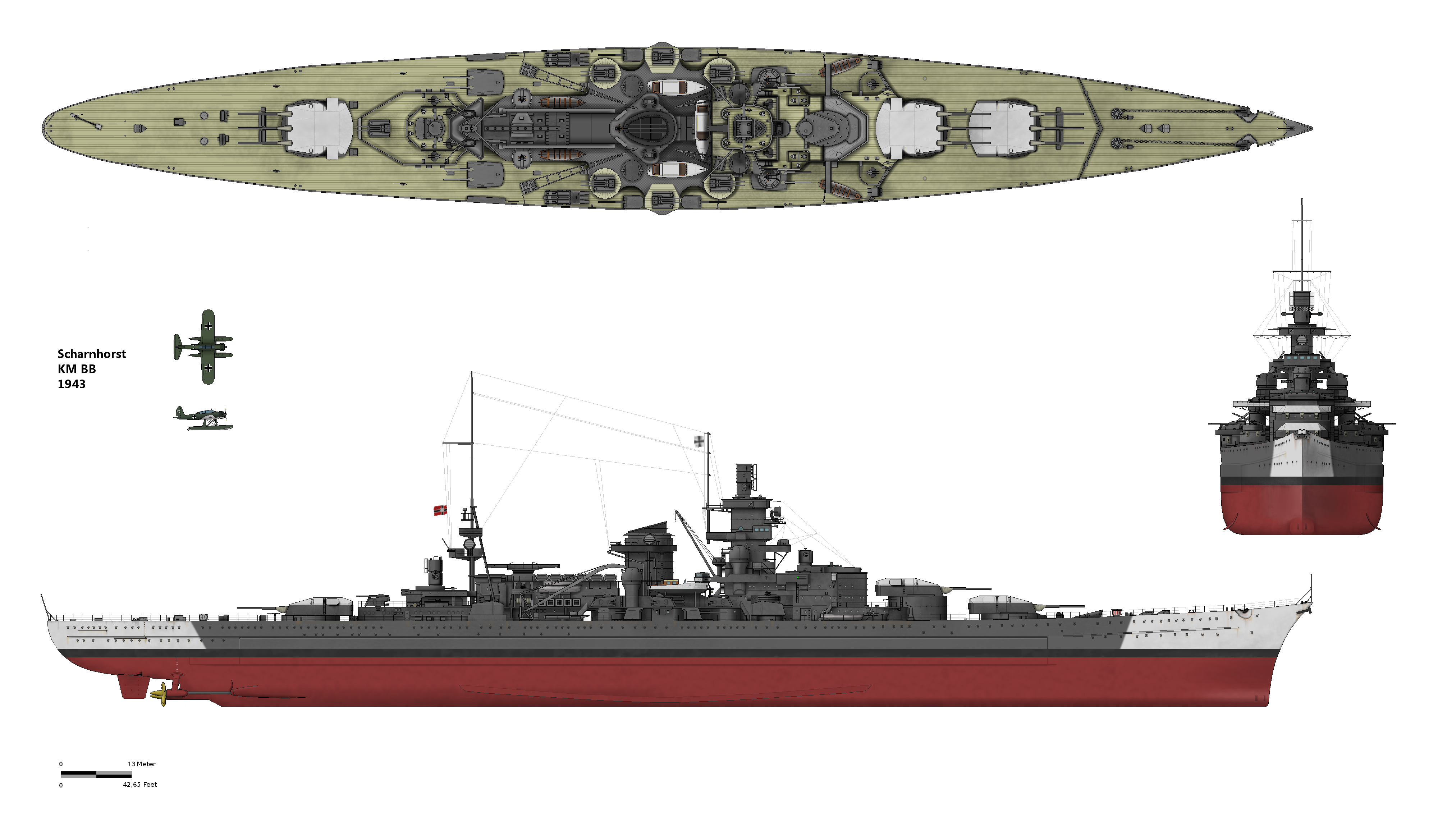

Scharnhorst was a famous World War II capital ship, the lead of her class, referred to as either a battleship or a battlecruiser of the German Kriegsmarine. This 31,500 tonne ship was named after the Prussian general and army reformer Gerhard von Scharnhorst and to commemorate the World War I armoured cruiser SMS Scharnhorst that was sunk in the Battle at the Falkland Islands in December 1914. Scharnhorst often sailed into battle accompanied by her sister-ship, Gneisenau. S

he was sunk after being engaged by Allied forces at the Battle of North Cape in December 1943.

The sisters - Scharnhorst and Gneisenau

The ship was built at Wilhelmshaven, Germany, launched on 3 October 1936, and commissioned on 7 January 1939. The first commander was Otto Ciliax (until 23 September 1939). After initial service, she was modified in mid-1939, with a new mainmast located further aft and her straight bow replaced by an "Atlantic bow" to improve her seaworthiness. However, her relatively low freeboard ensured that she was always "wet" when at heavy seas. The gunnery report after the engagement with HMS Renown reports serious flooding in the "A" turret that severely reduced its effectiveness.

Her armour was equal to that of a battleship and if it had not been for her relatively small-calibre guns she would have been classified as a battleship by the British. The German navy always classified Scharnhorst and Gneisenau as Schlachtschiffe (battleships). These two ships, considered handsome and fast (with a top speed of 31.5 knots), were invariably mentioned at the same time, often fondly being referred to as "the ugly sisters" because they prowled together and wrought havoc on British shipping.

Scharnhorst

Scharnhorst's nine 28 cm (11 inch; in fact 283 mm - 11.1 inch), main guns, though possessing long range and quite good armour-penetration power because of their high muzzle velocity, were no match for the larger calibre guns of most of the battleships of her day, particularly with the flooding and technical problems that were experienced. The choice of armament was a result of their hasty commissioning. If a later proposal to upgrade the main armament to six 38 cm (15-inch) guns in three twin turrets had been implemented, Scharnhorst might have been a very formidable opponent, faster than any British capital ship and nearly as well armoured. But due to priorities and constraints imposed by World War II and later the war situation, she retained her 28 cm (11 inch) guns throughout her career. Both Scharnhorst and her sister were designed for an extended range to allow for commerce raiding.

Operation Ostfront and Battle of North Cape

On Christmas Day 1943, Scharnhorst and several destroyers, under the command of Konteradmiral (Rear Admiral) Erich Bey, put to sea with the purpose of attacking the Russia-bound Arctic convoys JW 55B and RA 55A north of Norway. Unfortunately for the Germans, their orders had been decoded by the British codebreakers and the Admiralty were able to direct their forces to intercept. The next day, in heavy weather and unable to locate the convoy, Bey detached the destroyers and sent them south, leaving Scharnhorst alone. Less than two hours later, the ship encountered the convoy's escort force of the cruisers HMS Belfast, Norfolk, and Sheffield. Belfast had picked up Scharnhorst at 08:40 and 35,000 yards (32,000 m) using her Type 273 radar and by 09:41, Sheffield had made visual contact.

Under cover of snow, the British cruisers opened fire. Belfast attempted to illuminate Scharnhorst with starshell, but was unsuccessful. Norfolk, however, opened fire using her radar to spot the fall of shot and scored two hits. One of these demolished Scharnhorst's main radar aerial, disabling the set and leaving her unable to return accurate fire in low visibility. Norfolk suffered minor damage.

In order to try to get around the cruisers to the convoy, Bey ordered Scharnhorst to take a southeast course away from the cruisers. In the late afternoon, the convoy's covering force, including the British battleship HMS Duke of York, made contact and opened fire. Despite suffering the loss of its hangar and a turret, Scharnhorst temporarily increased its distance from its pursuers. The Duke of York caught up again and fired again - the second salvo wrecked the "A" turret, detonating the charges in "A" magazine which led to the same in "B" magazine. Partial flooding of the magazines quenched the explosions. No Royal Navy ship received any serious damage, though the flagship was frequently straddled, and one of her masts was smashed by an 11-inch (280 mm) shell.

At 18:00 Scharnhorst's main battery went silent; at 18:20 another round from Duke of York destroyed a boiler room, reducing Scharnhorst's speed to about 22 knots (41 km/h) and leaving her open to attacks from the destroyers. Duke of York fired her 77th salvo at 19:28. Battered and crippled as she was, her secondary armament was still firing wildly as the cruiser HMS Jamaica and the destroyers Musketeer, Matchless, Opportune, and Virago closed and launched torpedoes at 19:32. The last three torpedoes, fired by Jamaica at 19:37 from under two miles (3 km) range, were the final crippling blow.

A total of 55 torpedoes and 2,195 shells had been fired at Scharnhorst.

Oberbootsmannsmaat (Petty Officer) Wilhelm Gödde described the scene:

On the deck, all was calm and orderly. There was hardly any shouting. I saw the way the First Petty Officer helped hundreds of men over the rails. The Captain (Fritz Hintze) checked our life-jackets. Once again before he and the Admiral (Erich Bey) took leave of each other with a handshake. They said to us, "If any of you get out of this alive, say hello to the folks back home, and tell them we did our duty to the last."

Matrosenobergefreiter (Sailor) Helmut Backhaus describes the moment of sinking:

I stopped and turned in the water to get my bearings. It was then that I saw the keel and propellers. She had capsized and was going down stern first.

Blindfolded Scharnhorst survivors come ashore at Scapa Flow on 2 January 1944

Scharnhorst sank at 19:45 hours on 26 December 1943 with her propellers still turning. Of a total complement of 1,968 men, only 36 survivors - none an officer - were rescued from the frigid seas; 30 by HMS Scorpion and 6 by Matchless. Later that evening, Admiral Bruce Fraser briefed his officers on board Duke of York:

"Gentlemen, the battle against Scharnhorst has ended in victory for us. I hope that if any of you are ever called upon to lead a ship into action against an opponent many times superior, you will command your ship as gallantly as Scharnhorst was commanded today".

1 comment:

Warfare is a fascinating subject. Despite the dubious morality of using violence to achieve personal or political aims. It remains that conflict has been used to do just that throughout recorded history.

Your article is very well done, a good read.

Post a Comment